From the perspective of a supervisor and a recent student, we talked about research in – and through – music in an institutional context. We both believe that a doctorate in music is transformational, for a practitioner and a researcher, particularly when these two avatars are donned by one and the same person. Here we share a truncated version of our rather long and lively conversation.

Vanessa (V): We’ve talked a lot over the years about multiple identities, especially as an artist, academic. Within an institution this is exciting and complex, particularly in doctoral candidacy. We stopped having divisions in Doctorates between facets of artistry (composition, performance) because of the interwoven approaches that people use in their artistic processes.

Charu (C): True, artists doing different things has become the norm these days. In fact, it is rare to find someone who refers to themselves in just one role.

V: The training and approach of our professional doctorate (DMA) has now become part of the approach for PhD students. Once a PhD student was very focused on an historical, perhaps musicological perspective. Now embodied music-making is very much a part of a PhD as well. These days all QCGU HDR students are valuing their identity as artists, writers, thinkers, and collaborators.

C: I think we should acknowledge the plurality that is inherent in human nature to reconcile with the fact that a person can be an academic, a thinker, a philosopher and an artist rolled into one. I loved being part of the doctoral study. The experience was like an avalanche. You suddenly realise that you have all these things going on, that you have always had all these things going on, and that you finally have all these wonderful ways to unpack them!

Monteverdi Reimagined – PhD research by Charulatha Mani

V: What are your thoughts on the candidate-supervisor relationship and the process of learning in that equation?

C: I believe that a supervisor is a bearer of knowledge of the broadest strategies that one can employ to use one’s skills not only to make a scholarly document out of it but also to gain understanding of how to create viable projects that can speak to the arts sector and academia. It is vital to have that guiding voice that asks: “Why not read this, or why do you like that?” Or, “have you read Crispin, or Impett yet?” I have tried to get a handle on a few pressing questions on these occasions: How is it that people wear these many hats? What are the many research methods out there? How are other related projects in the field lending vibrancy and knowledge?

V: As a supervisor, I have seen many models over the years, and have understood that artistic research is everything but singular. It is focussed around each individual at the centre with questions, strategies and processes built around that person’s practice, so essentially it has to be bespoke for each person.

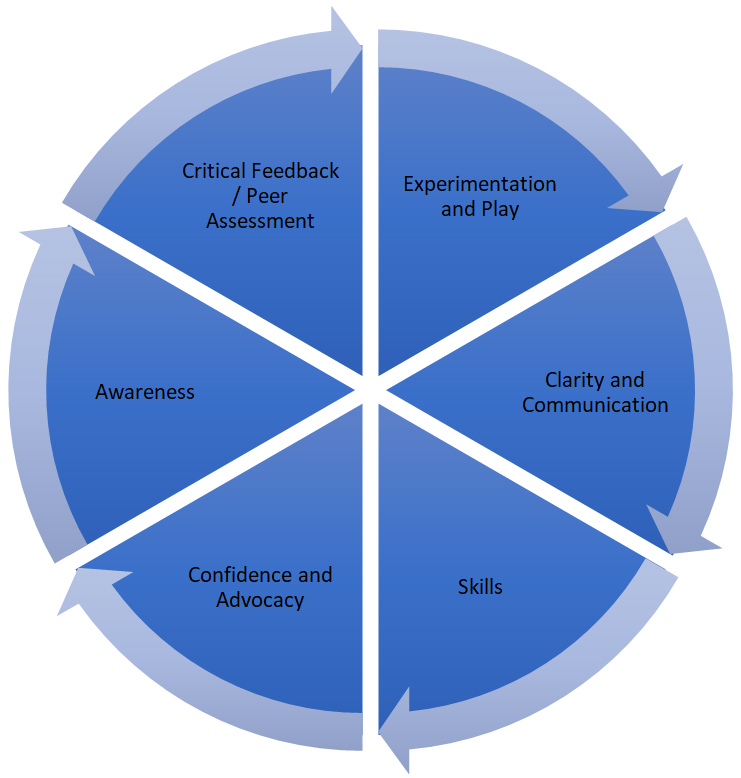

I have developed six categories of transformation in doctoral students based on 12 years of Doctoral supervision, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Six categories of transformation in doctoral students.

The first one is Critical Feedback and Peer Assessment. It is rare to develop a deep trusting relationship where you can say something to another artist about their artmaking that is quite fundamental, critical, and productive, especially as we are all experienced artists. Experimentation and Play, which is also permission – permission to play, to test out a new idea, to turn a corner, to be pushing into new areas.

C: Also, being experimental challenges exceptionalism and excellence. It takes the pressure off.

V: Clarity and Communication; I find that just the practice of repeatedly saying what one is trying to do is a good way to really understand what one intends to achieve. Awareness; an awareness that there are people working in parallel fields makes us feel connected to the world on a whole other level. Confidence and Advocacy – being the person that can speak up for the community, for artistic research, for the role of the academic in society, and for your research topic. The last one is Skills; developing written and creative skills. You are not static in your skill building during a doctorate, but nor are you driven by skill. These are the six areas that that I think are at play while undertaking a doctorate. Want to add anything or respond?

C: Awareness, for me, yokes to respect. When I look at the diverse communities and the wide variety of projects, I become aware of the importance of mutual respect and inclusivity in making a change for and through art. Among these six criteria, if I was to put anything on the top of the pile, it would be awareness and its linkage to interpersonal respect. Awareness is at the centre of everything.

V: I feel that Artistic Research is not different from other research in the university (science etc.) with the exception that we give privilege to our embodied knowledge. This tactile sounded knowledge becomes part of our literature.

C: This idea directly links to the “Human Library” concepts that Griffith has recently introduced. Research in many disciplines is now gearing towards respecting the embodied being with a life and lived experience as central to knowledge.

Vanessa Tomlinson and Charulatha Mani perform – Artistic Research Symposium with Darla Crispin, Brisbane, November 2018.

V: These old binaries between inside-outside, and academia and the world, become inter-permeable.

C: I think the binaries are breaking down in every possible sector of human existence. You don’t have to identify as a male or a female anymore, which is fantastic!

References:

Draper, P. & Harrison, S. (2016, August 11). Beyond a doctorate in music. NiTRO. Retrieved from https://nitro.edu.au/articles/edition-2/beyond-a-doctorate-in-music

Griffith University (2019, March 5). Borrow a human book [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://griffithlibrary.wordpress.com/tag/human-library/

Professor Vanessa Tomlinson is the Deputy Director of Queensland Conservatorium Research Centre and is program director of the Doctor of Musical Arts. In addition she is Head of Percussion and contributes to many different areas of the curriculum. Vanessa is an active performer, composer, improviser, curator and artistic director primarily working on large scale, site specific sound-based work.

Charulatha Mani has just submitted her PhD for examination under the supervision of Professor Stephen Emmerson and Dr Catherine Grant. She is a singer-researcher originally from Chennai, India, with interests across artistic research methods, historical and comparative musicology and gesture in music.