By Professor Lisa Grocott

Where co-design meets material making. SHEcity design workshop by Monash’s XYX Lab. Photo: Tina Dinh.

Thirty years ago, I had to repeatedly explain to my grandparents what I was studying at university – presumably, they felt about Design the way I feel when my kids tell me they want to be YouTubers when they grow up. Today, the litmus test for what people think design might be plays out every time I get into a cab. It’s enough to say I am a design professor to get through airport immigration, but the cab driver has time for the inevitable follow up question: what kind of things do I design? There is always an assumption that I design a “thing”.

My answer depends on how long I want this conversation to go on. I can say “communication design” without further explanation. Or I can say I design experiences and interactions by comparing what it is like to hail a cab versus ordering a cab, or how it feels to have bullet proof glass between us versus being offered a Mentos. If it’s a really long ride, I can talk about designing services and systems by comparing Google Maps to Waze, the autonomy yet insecurity of the gig economy, or the unintended consequences of midday traffic congestion when school kids use UberEats to deliver their lunch.

I studied design at an art school in the days when a designer was a sold-out artist. My counter narrative was to idealistically position the designer as functional problem-solver. Over the decades my perceptions are less reactive or romantic. Today we can hold the idea of designer-as-facilitator alongside the perception of designer-as-futurist. We can reconcile the philosophical belief that design operates in the realm of possibilities to craft preferred tomorrows with the pragmatism of co-designing with stakeholders as a strategy for community engagement. Design today is an inclusive practice that accommodates powerfully complementary orientations.

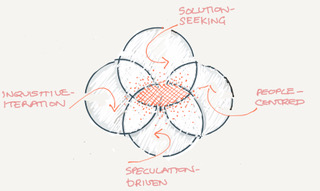

The Creative Tension of Designing. Diagram courtesy of author.

There is a process of pushing and pulling at the heart of designing. A creative tension that helps navigate between a material-oriented practice and a people-oriented one. A pragmatic push toward seeking solutions for real-world challenges and a poetic pull toward speculatively imagining never-before-seen worlds. This push and pull is what locates design as between art and psychology, between engineering and science fiction. The professional practice of a speculative designer can at times seem antithetical to that of an industrial designer and yet it seems critical to interrogate the ways we are the same and different rather than place ourselves in opposing camps.

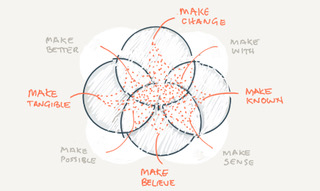

To leverage the dominant, enduring perception of designers as makers of things it is illuminating to see this creative tension not as a binary to be negotiated but as a field of making to be animated. In this way, we start to understand how convergent thinking drives solution-seeking and is complemented by divergent, speculative thinking. Across an expanded field of “making” we see that to make meaningful change, we need to first make ideas believable in order to make them possible. Similarly, we see how a people-centred orientation complements the material orientation of piloting and prototyping so we might value making sense through making tangible things with others. Here, it becomes possible to imagine a participatory design practice where bespoke artefacts leave sticky notes for dead.

Animating a Field of Making. Diagram courtesy of author

We know that today’s designers create services, experiences, interactions, games and systems as well as products. Yet defining design practice by the outputs limits an understanding of what design does. It can be illuminating to see beyond what we design to what we are making. Our tangible designs are the manifestation of what happens when we design for connection, for wellbeing, for justice, for clarity, for engagement, for play. To make sense, to make with, to make better, to make possible lays the foundation for the designers’ commitment to make believe, to make tangible, to make known, to make change. If design is really about crafting preferred futures, then our superpower may not be that we make tangible artefacts but that we make the conditions for change.

Lisa Grocott is the Director of WonderLab and a Professor of Design at Monash University. Before coming to Monash Lisa spent more than a decade at Parsons School of Design in New York. Lisa’s research specifically examines the contribution of the people-centred, speculation-driven practice of design in interdisciplinary collaborations with cognitive psychologists, education researchers and behavioural change experts. WonderLab is a co-design research lab that operates at the intersection of design, learning and play. This week she is most excited about the pop-up PhD at the heart of WonderLab where an international cohort roam the world for meet ups in different countries every year.