By Trent Jansen and Guy Keulemans

In this article we discuss models of design practice, based on three student projects from different program levels, the Bachelor of Design, the Master of Design (coursework) and the Doctor of Philosophy in Design, in the School of Art & Design at the University of New South Wales, Sydney. We discuss how student’s design-led approaches respond to key issues in the 21st century; cross-cultural knowledge exchange in a rapidly globalizing world, countering marginalisation that perpetuates coloniality, and a speculative design proposal for resolving the compounding problem of waste. Each of these projects arose through a designer-identity shaping process operationalised through critical self-reflection and conceptual modes of teaching and learning.

FIGURE 1: Melvin Josy, Vallam Bench, 2021. Image courtesy of Melvin Josy.

The most recent of these projects is contextualized by the pandemic (2020-2021), in which all our courses shifted online. For our Masters-level furniture and lighting design course students are encouraged to examine questions of locality, given that many are off campus, studying at home, abroad and unable to travel. We recognized that students might be situated in a culture familiar to them but unfamiliar to other students in their class, or vice versa. The brief provided fertile ground for cross-cultural knowledge exchange and the embodiment of local identity in design outcomes. Melvin Josy from Kerala, India, used his knowledge of Keralan methods for “sewn” boat building, a unique tradition with roots going back 5000 years ago, to design furniture adapted for computer-aided manufacturing (Fig. 1). The benches additionally refer to Indian material culture in their use of up-cycled sari fabric for the knot work, a detail that speaks to contemporary concerns for reducing waste through design. While these traditional methods of construction signify local values and ideas, Josy’s hybridisation of traditional and contemporary technologies potentialise new kind of efficiency, precision and formal innovation. His work suggests that such adaptions can help traditions endure, resilient to globalisation’s homogenisation effects. In the time of COVID, Josy’s design foregrounds the importance of knowledge exchanges and the benefits of harnessing cultural identity, despite the closures of international borders.

FIGURE 2: Ivana Taylor, Civilised Roots, 2019. Image courtesy of Ivana Taylor.

Bachelor of Design (Honours) graduate Ivana Taylor began her journey with textiles in the classroom of UNSW academic, weaver and living treasure of Australian craft, Liz Williamson. Taylor’s abilities with textiles augmented her studies in object design briefs concerned with responses to the waste crisis. Wrapping old furniture with textiles to reinvigorate their style – and to question our perceptions of value predicated on such senses of style – kickstarted her obsession with iterative making. Her Honours graduation project, for which she won the UNSW medal, concerned the typology of bush furniture as a metaphor for romantic, Anglo-Australian frontier narratives. Taylor juxtaposed furniture archetypes with wrapped organic textiles (Fig. 2), and visualised the layers of obscuration and myth-making wrapped around the raw accounts of Indigenous land dispossession and genocide in Australian post-colonial history. After graduation, Taylor became an Associate at the JamFactory in Adelaide, exhibited in Melbourne Design Week (Fig. 3) and was selected for Vogue Living’s VL50 list of top Australian designers in 2021, major achievement for a recent graduate. Taylor’s work demonstrates how conceptual methods of learning and teaching can produce agile graduates with the capacity to transition successfully into industry, even when the national craft sector is economically pressured.

FIGURE 3: Ivana Taylor, 2021. Image courtesy of Ivana Taylor.

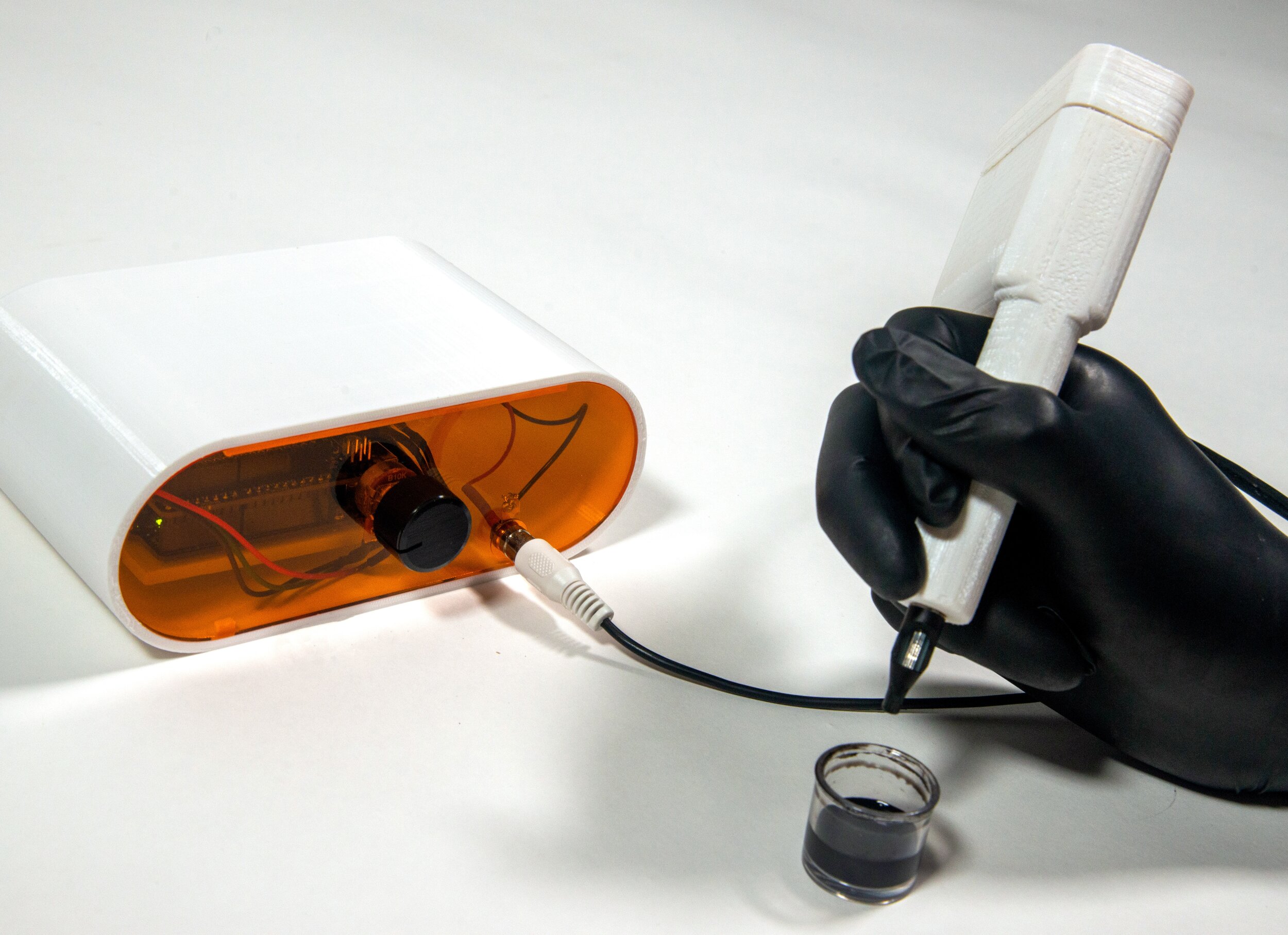

FIGURE 4: The Biorecycling Machine by Matt Harkness, PhD candidate, 2021. Image courtesy of Matt Harkness. Video: https://vimeo.com/524695662

Our third example focuses on what can happen when design is approached conceptually and analysed from the intersectional perspective of the significant issues of social and cultural inequity and the increasingly urgent problems of ecological degradation. Design PhD candidate Matt Harkness researches the phenomena of “makerspaces” and how they are characterized by systemic practices of privilege and waste.[1] Through a framework for understanding complex systems, Harkness illuminates the intersectional vectors that connect crises of social justice with crises of ecology, and issues of waste with the human body. His speculative critical design, the Biorecycling Machine (Fig. 4), is premised on the capacity for polylactic acid (PLA) polymer to theoretically break down in the human body. PLA is the main plastic used in 3D printing machines, wasted at the scale of the thousands of tonnes per year, and is also widely used as a medical plastic. Although PLA is extensively marketed as a “green” bioplastic that is both biodegradable and recyclable, these marketing promises are rarely met in practice. In response, Harkenss provocatively proposes a machine based on a tattoo gun that injects dissolved PLA into human skin. In framing the design as an option for “zero-wasters” of the future who are anxious about proliferating plastic waste beyond their own body. The Biorecycling Machine critiques the potential, real and radical limits of human actions necessary to resolve the waste crisis. As Matt explains in an interview for Fast Company, the designed was inspired by “Reduce-Reuse-Recycle” campaigns that place responsibility for waste onto consumers: “in the Biorecycling Machine project, this concept is taken to the extreme”.[2]

References

[1] Matt Harkness is jointly supervised by UNSW Associate Professor Katherine Moline and Dr Guy Keulemans

[2] Mark Wilson, This machine injects plastic into your skin to fight waste, Fast Company, April 21, 2021, https://www.fastcompany.com/90627273/this-machine-injects-plastic-into-your-skin-to-fight-waste

Guy Keulemans is a designer, artist and curator researching repair, reuse, materials and generative processes for environmental sustainability. Guy has degrees from Design Academy Eindhoven and the University of New South Wales, where he also lectures. He has exhibited in museums and galleries in the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Austria andTaiwan. Guy currently investigates transformative repair practices funded by an Australian Research Council Linkage grant with Design Tasmania, JamFactory and the Australian Design Centre.

Trent Jansen is a designer using his method of Design Anthropology to embody the values, ideas, attitudes and assumptions of targeted cultures in designed artefacts, proliferating often marginal cultural narratives through the medium of design. Jansen gained his PhD from the University of Wollongong and his Bachelor of Design from the University of New South Wales, where he now lectures. Jansen was co-founders of Broached Commissions and is represented by Broached Commissions and Gallery Sally Dan-Cuthbert in Australia, Gallery All in the USA and China, and Galleria Rossana Orlandi in Italy.